Cairo – Decypha: As the notion of oil approaching and crossing the $100 per barrel once again becomes increasingly improbable in the foreseeable future, economies that have traditionally relied on oil export revenues might be well advised to diversify their economies away from oil thus ensuring a stable revenue portfolio. None-more-so than Saudi Arabia where 80% of government revenues are generated from oil production. Oil also accounted for around 76.9% of all of the country’s exports by the end of 2015. It also shapes 55% of the country’s GDP.

The current status

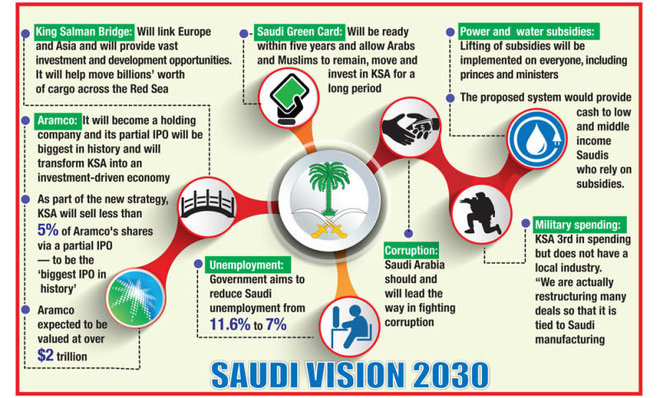

To try to increase the contribution of non-oil FDI to GDP as well as account for a bigger portion of government revenue, Deputy Crown Prince, Mohammad bin Salman Al Saud, formulated the Saudi Vision 2030 and subsequent National Transformational Plan (NTP), both of which aim to create a strong, and stable, Saudi economy as well as give more stability to public finances mainly through diversifying Saudi Arabia’s economy away from oil. By 2030, the non-oil sector should contribute about 50% of exports. For this to happen, deep reforms will be essential to shift the investment environment from one solely attractive to oil investment to one that attracts a diverse range of non-oil investments including textiles and electronics.

This diversification is coming at the right time as Saudi Arabia’s oil-dependent economy has taken a strong hit as global oil prices took a nose dive to reach a low of $35 in early 2016. This caused the country’s fiscal surplus of 13.6 % of GDP in 2012 to turn into a fiscal deficit of 17.3 % in 2016. The current account also recorded a deficit equal to 9.5 % of GDP by the end of 2016 compared to 22.5 % surplus in 2012.

To pay for this deficit the government used its foreign currency reserves which dropped from $756 billion to $ 506 billion between mid-2014 and Feb 2017. Saudi Arabia was spending an average of $10 billion a month to plug this deficit, according to a Financial Times article published early 2016. This deterioration, however, didn’t impact GDP growth which was 3.5 % in 2015 compared to 3.6 % a year earlier. Since the Arab Spring in 2011, Saudi’s GDP growth rate varied greatly from 5.2 % in 2012 to 2.7 % in 2013.

The 2030 plan and FDI

To save government finances from further deteriorations, the Saudi government is looking to attract a lot of new non-oil FDI to stabilize the country’s portfolio with the guidance of the Vision 2030 and NTP. As it stands, Saudi Arabia total FDI stands at $8.1 billion in 2015 compared to $8 billion a year earlier. Saudi officials have said in several media sources that they are aiming to double the current overall FDI figures by almost solely attracting non-oil FDI by 2030. To add $8 billion-worth of non-oil investments over current levels, Vision 2030 will be looking to economic zones with special regulations and stipulations. Each zone will focus on attracting either financial, logistics, tourism or manufacturing investments. The first such zone will be the $ 10 billion financial hub with a direct connection to King Khalid International Airport north of Riyadh. The Vision 2030 aims to increase non-oil revenues from SAR 199 billion in 2016 to SAR 1 trillion ($266 billion) by 2030.

The vision also talks about improving education and training, especially university education to eradicate the skills gap between graduates and employers. It also wants to increase women’s participation in the economy from 22 to 30%. Historic, cultural and natural location tourism especially along the Red Sea coast should also see noticeable reforms and hence investments.

As it stands, the kingdom’s biggest FDI investor is the UAE owning 17 % of foreign companies. It is followed by the USA with 15.2 % of companies. Japan, France and Kuwait comprise the majority of remaining FDI bulk, according to Jeddah Economic Gateway, a government body. The push towards a more diverse economy will open the door to investors coming from other economically-diverse nations to expand their investment portfolio in the country, changing its FDI composition. The rise in non-oil FDI ultimately aims to increase the GDP growth rate from the current 3.5 % to 5.7 % by 2030. Unemployment is also targeted to drop to 7 % from 11.6 %. Vision 2030 also aims to achieve a budget surplus in all accounts in the national budget.

Vision or reality: What experts say

Market observers agree that while Saudi Arabia is a ripe economy for much more non-oil investments, there must be a strong political push from the top to successfully attract non-oil FDI to a place where oil investments have always dominated.

For Andy Critchlow, News Editor at Telegraph Media Group, talking to CNBC in April, the vision as it is written will not attract sufficient non-oil FDI to solve Saudi Arabia’s oil-dependency problem. In the Saudi Vision 2030, “they barely scratched the surface of what is needed,” he said.

Mohamed el Erian, Chief Economic adviser at Allianz, in May 2017, was more optimistic about attracting FDI under Vision 2030 and the accompanying NTP. However, he points out that the plan “will not be without its risks,” he said. The major one is that transformational plans in general become trickier to implement the bigger the scope and scale because legacy systems become harder to change the deeper the reforms are.

Crispin Hawes, Managing Director of London-based Teneo Intelligence, believes that this vision has sufficient positive points to attract non-oil FDI. “It’s very hard to argue that Saudi economic policy is worse than it was two years ago,” said Hawes to Bloomberg last March. However, both agreed that the Vision 2030 implementers will face a lot of resistance during implementation.

Reform measures taken

A vital component for the government to go through with the Vision 2030 is the Aramco IPO, which will be pivotal in financing this plan. “The [National Transformation Plan] has many legs, but the initial public offering of Aramco is a key one,” said Energy Minister, Khalid Al Falih, speaking on the sidelines of the World Economic Forum annual meeting. "The income from the IPO will allow the Public Investment Fund of Saudi Arabia (PIF) to have more funds as it goes global, so [the IPO] is a key issue for the transformation." Based on government estimates Aramco should be valued at $2 trillion, and the plan is to float 5% of it, the public offering should bring in around $100 billion to the national treasury. It is still unclear what will be the investment priorities of those $100 billion. Also unclear is when this IPO will happen. Predictions vary greatly from a few months to sometime in 2018. The other source of financing the vision is the Saudi sovereign fund that, among other things, will manage the public portion of the Aramco IPO, which if happens will be the largest in the world. According to Prince bin-Salman in April 2016 to Bloomberg, assets managed under the fund could reach $ 300 billion in addition to the current value of the fund which is about $200 billion. “In this way we will have a Public Investment Fund with a size exceeding $2 trillion, approaching $3 trillion,” he said.

Once these funds are secure, new non-oil investors will be operating in a very different Saudi Arabia compared to veteran investors as the government has been heavily reforming its economic regulations and policies. These reforms started last September when the government cut salaries and benefits of around 3 million public-sector employees--almost two-thirds of the country’s workers. This immediately saved $ 17 billion. However, these proposed reforms sparked fears that certain factions from the Saudi society, including hardline clerics and low-income Saudi nationals would take a hardline against these reforms. These fears prompted Prince Salman to tell Foreign Affairs magazine that “punitive measures would be considered for any clerics who incited or resorted to violence over the plan,” reported Reuters in an article published last January. The state also started increasing the prices of utilities such as water, electricity and fuel, to cut the subsidy budget. They also applied a 2.5 % tax on unused land, $ 23 visa for incoming foreigners and a 5 % VAT implemented January 2018 along with additional taxes on some luxury items such as chocolate.

There were also changes in ministers where veteran ministers such as the 20-year veteran minister of finance Ibrahim al-Assaf, were replaced by the Head of the Capital Market Authority, Muhammad al Jadaan, who is younger and never held a ministerial position. The government also restructured the cabinet. It separated water from electricity, commerce from investment and electricity from fuel. These moves aim at creating a more efficient cabinet that can take better decisions, faster. Manufacturing investors have also asked that they want their own ministry to solely address their problems quicker. However, no announcement was made regarding the separation.

Potential challenges

Despite the changes, however, new non-oil investors will still face incumbent risks that Vision 2030 hasn’t addressed them with enough detail. One such risk is the constant interference of the Saudi government in different aspects of businesses such as hiring women or forcing companies to hire Saudi nationals instead of foreigners (A long-standing policy called “Saudification” of jobs). This is problematic because Saudis might not be as qualified as foreigners given the local education system focuses on religion rather than practical skills. Saudis will also unlikely want to work in blue-collar jobs given they come from rich backgrounds and therefore expect to work in white-collar jobs from the start. Another red flag was the royal decree announced in March to lower the tax rate specifically for Aramco from 85 % to 50 %, a move which observers say is aimed squarely at raising the company’s valuation to $ 2 billion before going public with it. Also, the Saudi government has been delaying payments to some of its contractors, including the Binladen Group and Saudi Oger.

One of the bigger challenges for new and existing non-oil investors who want to invest in Saudi Arabia will most likely be that the Saudi Riyal has been pegged to the dollar for 30 years or more. That was never a problem given that oil has a global price, similar to all other commodities, and therefore oil investors flocked to the country because of its reserves and not because of lower production costs. This changes massively with non-oil investment, since consumer prices and production costs are vital in the competitiveness of locally-made products in the global market. A case in point is Egypt always highlighting how low manufacturing and investments costs are with low labor salaries, subsidized energy to factories and more recently the devaluation of the pound by more than half versus the dollar. For the Saudi government the decision to free float the Saudi Riyal will introduce a new element of uncertainty to the local economy as its value will now swing based on supply and demand. This will most likely make it more of a political decision rather than an economic one.

By Tamer Mahfouz